From the Field: Agronomy Notes-Vol. 2, Num. 7

go.ncsu.edu/readext?460089

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲April 18th, 2017-

The 2017 transplanting season began in earnest last week. Social media posts have revealed that producers from the Border Belt northward into the Upper Coastal Plain and westward into the Sandhills were off and running very early. The extended forecast looks very good, as we should see temperatures climb into the mid-80’s this week. Recent soil temperature measurements at research sites in Columbus County and Guilford County have also been very good with recorded temperatures ranging from 68 to 74 degrees at a depth of four to five inches. Given the rain we experienced last week, I can’t think of better environmental conditions to start the field season. With that, it appears as though the 2017 tobacco season is off to a fine start.

As the field season kicks off, it’s worth circling back to a brief discussion of auxin herbicides and a few considerations that should be made for tobacco producers.

First and foremost, as an allied industry, we have to stick to our guns on the fact that auxin herbicides and tobacco do not mix. The term “auxin herbicide” is a general name used to classify materials such as 2,4-D, dicamba, picloram, and aminopyralid. This isn’t anything new for anyone with any experience in our industry. Due to the unique nature of the industry, tobacco losses from auxin herbicides cannot only be measured in pounds per acre but also in marketing opportunities. Auxin herbicides are NOT labeled for use in the production of tobacco; therefore, if a drift event (physical or vapor) occurs, residues of a pesticide(s) not labeled for production can be found in/on cured leaves. Simply stated, the purchasers of our tobacco do not want tobacco that has come into contact with a chemical not approved for use. It is my firm belief that the damage done to the reputation of US tobacco because of illegal residues is much greater than that done through physical injury that can reduce leaf yield per acre. This particular fact is even more concerning for organic tobacco producers, as a drift event could jeopardize organic certification. This scenario would likely require a three year interval for organic re-certification.

What does this mean for you as a producer of US tobacco? It means a lot of things. First, it means that as you begin to think about weed management in other crops you need to be a little more considerate with how certain practices can influence tobacco. One example that comes to mind: auxin herbicides are great burndown materials because they are relatively cheap and very effective. They are in fact so great that we’ve observed 2,4-D injury in two tobacco greenhouses within the past week (Figures 1 and 2). Given the warm temperatures, strong winds of March and April, and the close proximity of herbicide application, it’s not all that surprising that this happened. In one case, the amine formulation of 2,4-D was used in order to reduce volatility and greenhouse curtains were raised to prevent physical drift into the house. Volatility is most likely culprit in this case, which brings us to another great point: auxin herbicides (primarily 2,4-D and dicamba) are known to be extremely volatile. Sure, there are different formulations of 2,4-D and dicamba that are less volatile than others (amines are less volatile than esters, choline is less volatile than both amines and esters), but the fact remains that these materials are still more volatile and cause greater injury in tobacco than other burndown herbicides such as glyphosate, glufosinate, atrazine, and paraquat. This fact touches on the need for communication with neighboring farmers, as it is generally a good idea to know what crops are planted in surrounding fields and what their susceptibility to herbicide chemistries might be. To help with grower communication, the NCDA&CS has made available an online Drift Watch tool where sensitive crops (among other things) can be registered. Farmer use is completely voluntary, so personal communication is still strongly recommended. Access the Drift Watch tool. (http://www.ncagr.gov/pollinators/Driftwatch.htm).

Figure 1. 2,4-D vapor drift injury to tobacco seedlings. Normal plant on the left, injured plant on the right (necrotic stem and club shaped bud leaves).

Figure 2. Injury from physical 2,4-D drift onto tobacco seedlings. Note the wavy/serrated leaf margins and well defined leaf tip.

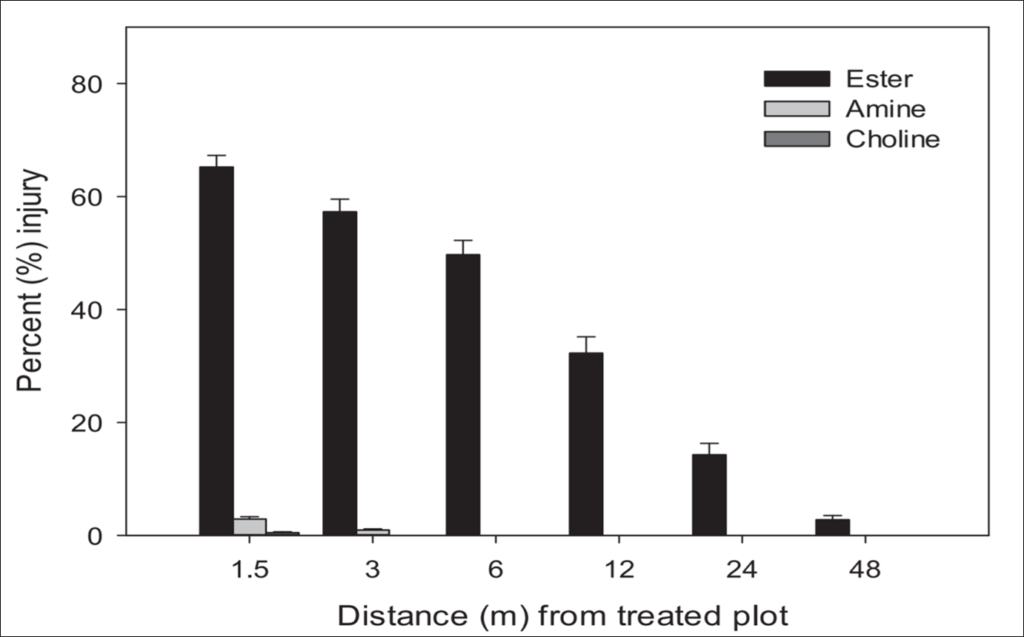

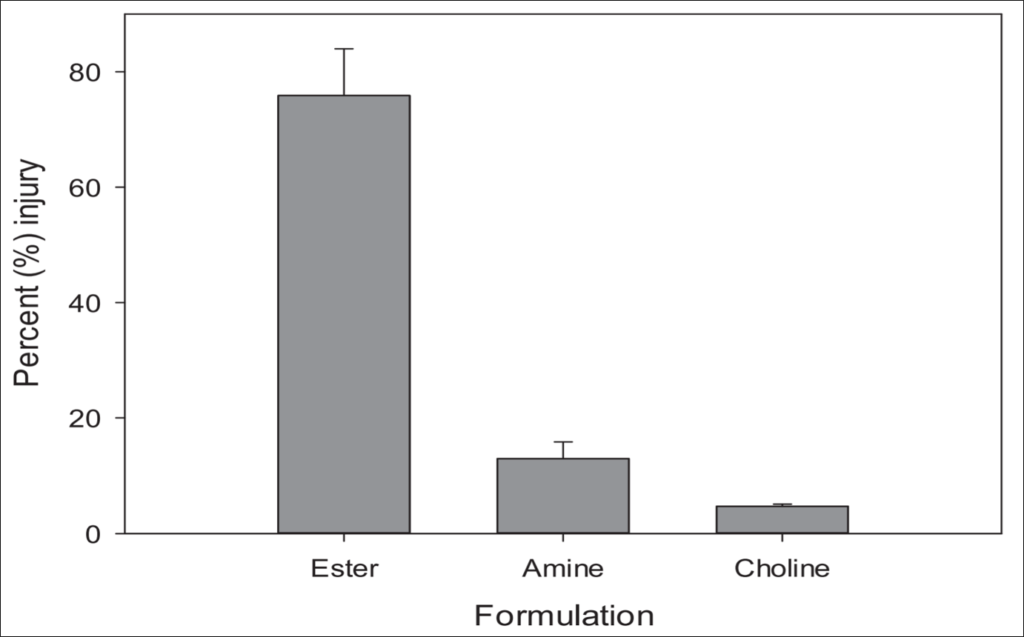

In a study conducted in Southern Georgia, Sosnoskie et al. (2015) evaluated the volatility of three 2,4-D formulations (ester, amine, and choline) over a 48 hour period. It was ultimately concluded that plant injury was greatest following the ester application (Figure 3). Injury was much less frequent in amine and choline treatments, specifically as distance from the point of application increased (Figure 3). One interesting point of consideration is that plant injury was observed in the ester treatment as far as 48 meters (157 feet) from the area of application. Injury from the amine and choline formulations were not observed at distances beyond 3 meters (9.8 feet) and 1.5 meters (4.9 feet), respectively (Figure 3). Additional observations were made inside the treated areas using high-tunnel houses that covered the bare ground, which allowed for maximum exposure to the herbicide vapor. Again, the ester formulation produced the highest injury (76%), followed by amine (14%) and choline (5%) (Figure 4). The overall takeaway from the data presented is that 2,4-D ester formulation is much more volatile than either the amine or choline formulations. That does not mean that amine and choline formulations are not volatile, only that they are less likely to volatilize as much as the ester. Considering that choline formulations will be required for application to 2,4-D tolerant crops, there appears to be a reduced threat from volatility and that off-site injury from choline is not likely to be more severe than that from the amine.

Figure 3. Effects of 2,4-D formulation and distance (m) from the treated plots on maximum cotton injury (%) for the 0 to 48 hour exposure period at 21 and 28 days after application.

Figure 4. Maximum injury (%) for cotton exposed to 2,4-D volatiles for 48 hours under plastic tunnels at 21 and 28 days after application.

Specific to tobacco, simulated physical drift rates of 2,4-D (1/2, 1/8, 1/32, 1/128, and 1/512 of 0.48 lbs ai/acre) have been reported to reduce tobacco yield from 200 to >1,000 pounds per acre. Injury in these studies ranged from a low of 5% to >70%. However, 2,4-D is not the only herbicide that creates drift concern. Results from treatment of dicamba (1/2, 1/8, 1/32, 1/128, and 1/512 of 0.25 lbs ai/acre) and glufosinate (1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 of 0.54 lbs ai/acre) are similar. Simulated drift of dicamba and glufosinate resulted in a loss of >1,200 lbs/acre as rates increased. The take home message is that physical drift of these materials is detrimental to tobacco growth and great care should be taken to prevent it. Selected pictures from this study are included below (Figures 5a-7c). Vapor drift was not evaluated in these studies; however, I’m confident that we’ll generate this data in the coming seasons through controlled research.

The bottom line is this, as a farmer you have a number of tools at your disposal for weed management and NC State University has provided thorough training for how these tools should be managed; therefore, it is best to follow the guidelines put forth by N.C. Cooperative Extension. Crop injury and the potential for yield and value losses are one issue; however, we must go beyond those losses in tobacco production. As was previously mentioned, there is even greater concern to the chemical residues that are left behind following a drift event. The bottom line is that buyers, manufacturers, and customers do not want them. Therefore, if you suspect that drift, either physical or vapor, has occurred, it is in your best interest to contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension Agent for assistance with diagnosis. In addition, it is strongly recommended that you speak with anyone purchasing your tobacco as it is much better to be up front about the issue than for it to be found at the point of sale or after.

Lastly, additional reading material from the University of Tennessee and the University of Kentucky are included. The links below are to Extension publications that might aide in the prevention and/or identification of drift events. These publications are primarily focused to burley tobacco; however, the information is the same for flue-cured.

Preventing Off-target Herbicide Problems in Tobacco Fields:

https://ag.tennessee.edu/herbicidestewardship/Documents/prevention_tobacco.pdf

Diagnosing Suspected Off-target Herbicide Damage to Tobacco:

https://ag.tennessee.edu/herbicidestewardship/Documents/diagnosing_tobacco.pdf

Dealing with Chemical Injury in Tobacco:

http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/agr/agr158/agr158.pdf

Reference:

Sosnoskie, L.M., A.S. Culpepper, L.B. Braxton, and J.S. Richburg. 2015. Evaluating the Volatility of Three Formulations of 2,4-D When Applied in the Field. Weed Technology 29(2):177-184.